Tagged: 1940s

Baseball as Civic Life

This winter has been pretty brutal, and I find myself with that familiar longing for Opening Day. I’m ready to hear the sound of a bat cracking instead of the scrape of a snow shovel carving narrow paths.

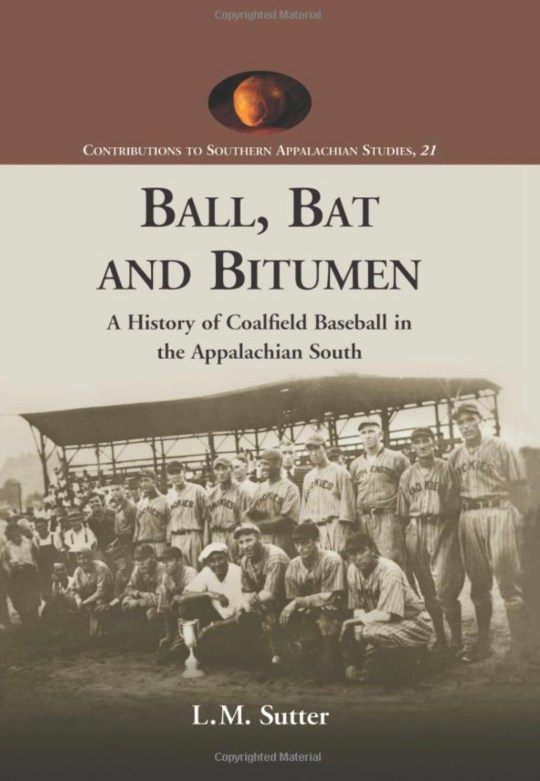

In my last post (yes, it’s been embarrassingly too long), I mentioned I was reading L.M. Sutter’s book, Ball, Bat and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South.

I picked it up because I wanted to better understand Stubby’s world as a young man. As I’ve spent more time digging into my family history (with roots that run deep in the coalfields), I’ve come to realize how important baseball was in creating a shared civic life. It wasn’t just a game. It was a gathering place, a language, a point of pride.

In her book, Lynn writes about how baseball parks were often built on the only flat ground available in coal towns. In places where people lived on steep hillsides and every usable acre mattered, carving out a diamond was a deliberate choice. What a town chose to make space for said a lot about what it believed mattered.

That idea unlocked something for me about Stubby.

According to The Dad, Stubby wrote about sports because he believed deeply in civic pride. He understood that baseball didn’t just entertain. It gave towns a shared story to rally around. And Stubby knew that covering sports was a way of saying this place matters—and the people who live here matter.

If you’ve been around this blog for a while, you already know I’m a Cincinnati Reds fan. Opening Day here isn’t just a game; it’s a civic holiday, full of ritual and promise, and the hope of summer just ahead.

And that connection isn’t accidental.

As Lynn writes, “A lingering Appalachian loyalty to the Cincinnati Reds stems from the frequency of that team’s visits to the coalfields and the intrepid spirit that carried the players into some of the most distant hollows.” One of the reasons The Dad says he moved to Cincinnati was because Stubby took him to Reds games when he was a kid.

It is all intertwined.

The small community baseball teams that Lynn documents, like the Dante Bearcats, Raleigh Clippers, Norton Braves, Hazard Bombers, Knoxville Smokies, St. Charles Miners, Derby Daredevils, Appalachia Railroaders, Middlesboro Blue Sox and McDowell County All-Stars, are gone now. What remains are the stories of what those teams once gave their towns.

As Lynn writes, “Television was a juggernaut that would reduce the minor leagues to mere nurseries for the majors, no longer legitimate sports options in and of themselves.” Before television, baseball had to be seen in person, and your local team was the game. Once fans could watch major league teams from their living rooms, the emotional center of the sport shifted away from hometown diamonds.

For places built around those diamonds, and for writers like Stubby who understood what they meant, what was lost was much more than just baseball.

~Melissa

Kentucky Derby Diamond Jubilee – 1949

In 1949, Stubby attended the 75th Anniversary of the Kentucky Derby in Louisville in 1949. As Eric Crawford writes

The Kentucky Derby has always been a writer’s event. At the Derby, bloodlines come first, but story lines are a close second. Great writers, some of the best, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Hunter Thompson, took their turns penning descriptions of the great spectacle.

Let’s not get too carried away here comparing Stubby to these literary giants. But the ole man did attend and got him some killer sway.

A pair of Diamond Jubilee Commemorative Glasses

and a cool souvenir book

And we’ll end with sage advice from Stubby himself from his Press Box column, May 3, 1936 …

Happy Horsing!

~Melissa

Bird dog for the Braves

Since we’re in the dead heat of July, let’s continue with the boys of summer. In the 1940s, Stubby was a scout for the Boston Braves, and in 1948, he attended the World Series where the Cleveland Indians ultimately beat the Braves in the 6-game series. The Braves franchise moved to Milwaukee in 1953 and then to Atlanta in 1966.

Thanks to Larry: “Currence was a scout for the Braves when they were still in Boston and a keen judge of talent. He referred to the assignment as being a “bird dog” for the Braves in the decade before they moved to Milwaukee.”

Photo details: Holy publicity shot, batman! As a practitioner of the public relations arts, I can spot a staged photo at 10 paces. But I like this one. These guys are committed. Kudos on the acting job, fellas. My fav is the flag. It’s laminated to give it that perfect summer breeze stiffness. I’m not sure who else is in this photo. If you do, let me know in the comments.

~Melissa

P.S. I’m excited to be heading to the Reds vs. Diamondbacks game tonight. The Dad says baseball was Stubby’s favorite sport, as it is mine. I’d like to think if Grandpa Stubby was around, we knock back a few cold ones and he’d regale me with tales of the Bambino and the good ole days.

Breaking The Dad’s heart over Sam Snead

So I broke The Dad‘s heart today when I failed to recognize who was the gentleman on the left. “That’s Sam Snead,” he said, peering over his glasses at me.

“Uh, who’s that?”

I’m sure you know Slammin’ Sammy, because you know everything. He did some things and became the head pro at Greenbrier in 1944. I’m not sure exactly when and where (probably Greenbrier) this photo was taken, but Stubby is younger because he still has color to his hair.

Check out some more Currence Family Memories of Sam Snead. And if you know who the gentleman is in the middle, please let me know if the comments.

~Melissa